Thomas Stevens was born in 1828 in Foleshill, near Coventry. He was interested in ribbon making at a young age and established his own weaving business in 1854. He was soon experimenting with the idea of producing multicolour pictures on his Jacquard looms. His earliest products (from 1862) were silk woven bookmarks. They were an instant success and within 15 years he registered 900 different designs. In the mid 1870s he was working on his first picture designs which he presented to the public at the York Fine Art Exhibition in 1879. Over the next two decades he could offer nearly 200 different designs with such variety to appeal to all tastes. In addition, he was producing all sorts of novelties that included valentines, Christmas and birthday cards, badges for schools, masonic and friendly societies. A London branch was opened in 1878 to cope with demand. Thomas died in 1888 and his two sons took over until the business became a private limited company in 1908. The Stevengraph Works continued production until 1940 when the building was completely demolished in the Coventry blitz.

Stevengraph Pictures and Portraits:

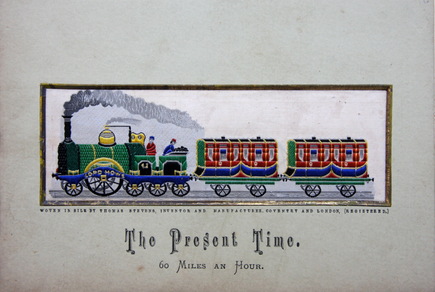

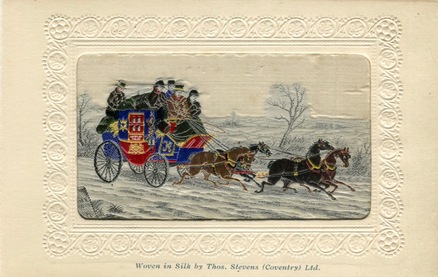

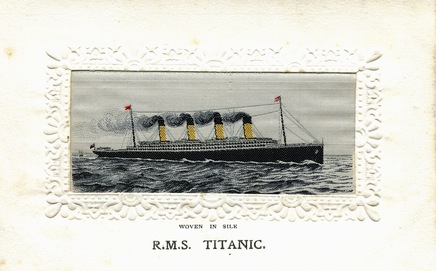

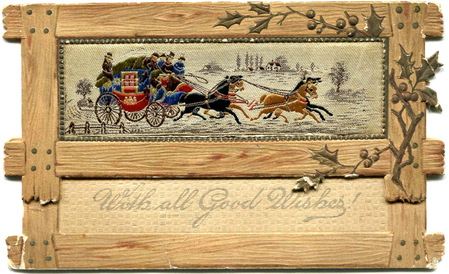

The most prolific period was between 1879 and 1905. Many categories were covered including royalty, military, jockeys, politicians, sportsmen and notables. The first portraits were produced around 1886. The scenes included buildings and exhibitions, historical and classical subjects, hunting, sports, ships, fire engines and trains all providing a flavour of the late Victorian period.

Silk Woven Bookmarks:

Stevens produced the first multi-coloured bookmarks in 1862. From then until the early 1900s he registered more than 900 different designs of which around 750 have been recorded to date. The collection ranged from small ones (at one penny) to large ones ‘for pulpits’ for as much as 15 shillings each. The designs included celebrities, exhibitions, local scenes, scripted texts, hymns, and a large range of birthday, Christmas and valentines for all occasions. Some had verses from poets including Wordsworth, Elliot, Shakespeare, Byron, Burns, Moore and Eliza Cook.

Silk Woven Postcards:

Silk woven postcards were not accepted by the Post Office until 1903.The Stevengraph company was quick to produce a wide variety of silk postcards often using existing Stevengraph designs. A rival, the W.H.Grant company in Coventry, was able to produce more designs, but Stevens found a niche market for ship pictures and ‘Hands Across the Sea’ flag cards.

Stevens Novelties “Stevensalia”:

Stevensalia is defined as ‘all the novelties produced by the Stevengraph Company that are not Stevengraph portraits and scenes and not Stevens bookmarks or postcards’. Included are valentine, birthday, New Year and Christmas cards, perfumed cards, printed cards, fringed cards, plush cards and folding cards. Then there are book cover panels in silk, fans, pin cushions, needle cases, fancy boxes, and numerous other items.

*A note on names: Stevengraphs (not Stevensgraphs, Stevenographs,or Stephengraphs ) refer to the pictures and scenes. Bookmarks were originally called ‘illuminated book-markers’ or ‘textilographs’ in the 1860s but subsequently were referred to as Stevengraphs until 1879 when the scenic pictures were made. The latter became Stevengraphs and the bookmarks were just ‘Stevens Bookmarks’. Postcards, first issued in 1903 were always called ‘Stevens Postcards’. In recent times ‘stevengraph’ has, for better or for worse, become a generic for any silk woven item.

The Stevengraph Collectors Association

The Stevengraph Collectors Association was founded in 1954 by Lewis Smith in Irvington-on-Hudson in New York State and a number of other individuals who were interested in silk weavings produced in the latter half of the 19th century. The group was especially interested in the works of Thomas Stevens.

The purpose of the Association is to provide a forum for members to learn more about Stevengraphs and to exchange information about them. Over the years, the Association has compiled an international archive regarding the history, origin and value of Stevengraphs.

The SCA publishes a quarterly newsletter which contains information regarding rare finds, prices of recent sales, member activities and information regarding items from silk weavers other than Stevens.

Members (and non-members) are encouraged to contact board members if they have any specific questions about Stevengraphs. The SCA charges a modest annual subscription which offsets expenses (postage, printing etc). If you are interested in joining please contact us. A free sample SCA-News can be emailed on request.

The SCA maintains close ties with the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum (in Coventry), the Macclesfield Silk Museums (in Cheshire), The Newberry Library (in Chicago) and the National Silk Art Museum (Weston, USA). The following pages provide information on the

Thomas Stevens Company, how Stevengraphs were made, buying and selling, care and preservation, as well as galleries of Stevengraph pictures (portraits & scenes), Stevens postcards and bookmarks and a selection of other novelties (‘Stevensalia’) which the company produced.